Originally published in Now Then Magazine

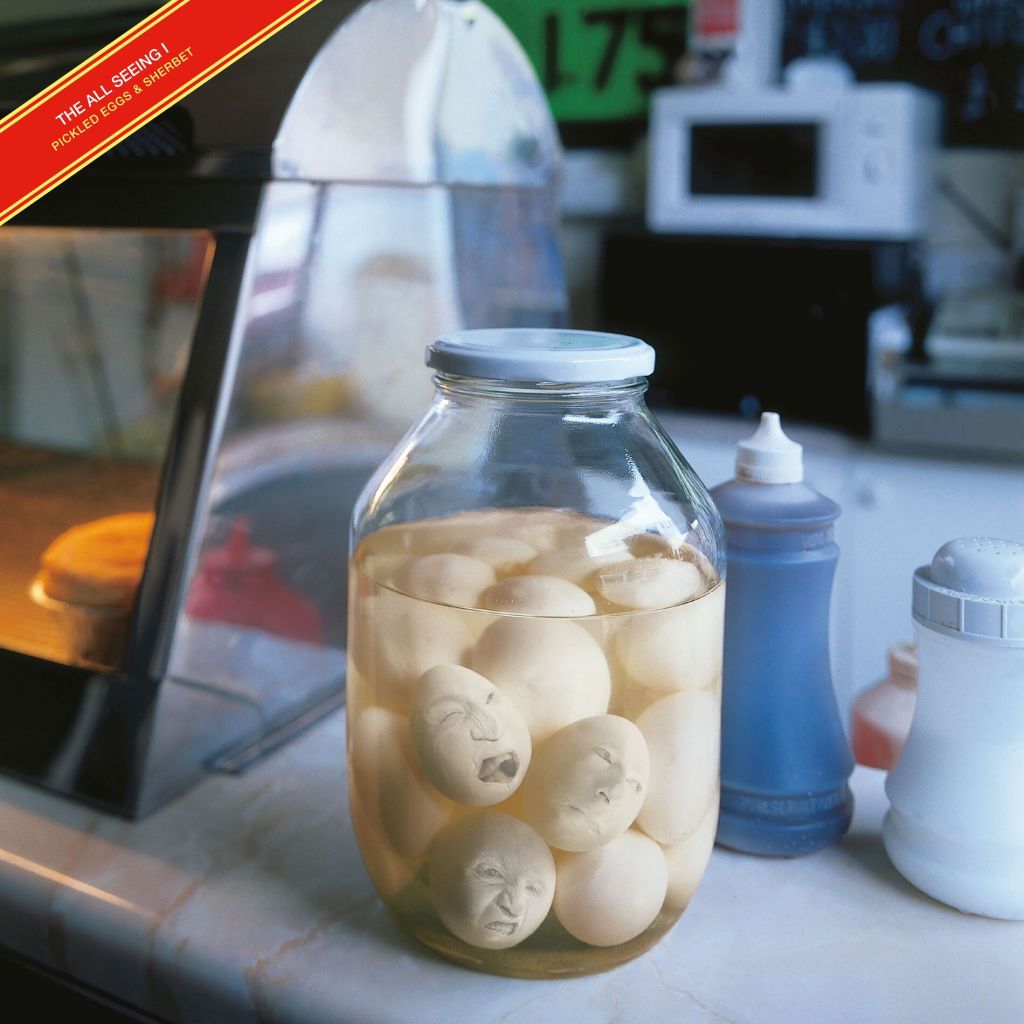

What connects Nether Edge, Britney Spears, and a trio of anthropomorphic eggs? It can only be Pickled Eggs and Sherbet, the first and only album released by Sheffield’s The All Seeing I. Featuring a motley crew of local talent – from Tony Christie to Phil Oakey of Human League fame – and with lyrics penned by Jarvis Cocker, the album is a gloriously weird concoction of crooners, breakbeats, synths and samples. It’s part off-kilter electronica, part working men’s club cabaret.

Now freshly remastered and out on vinyl for the first time, the reissued Pickled Eggs and Sherbert has cast fresh light on the 1999 album with a variety of outtakes and remixes. Speaking with Dean Honer and DJ Parrot ahead of the re-release, I ask them how it felt revisiting songs they made over two decades ago.

“You don’t really go back to it after you’ve made them,” says Honer. “It was quite interesting to hear how weird and lo-fi and strange-sounding it is overall as a record. Looking back at it, you think of it as a pop album. But it’s actually quite an experimental, weird little album.”

Some of that eccentricity comes from the production, with easy listening entertainers set against abrasive synths and electric guitar. I ask if there is any nostaglia for the way electronic music was made in the late 90s, with the internet still in its infancy, and artists wrangling with arcane hardware to extract, manipulate and compile sounds out of pre-existing material.

“The ‘Beat Goes On’ sample, that was just something that Jason bought from a junk shop”, he gives by way of an example. Whatever ease has been brought by modern technology, it has come at a cost: “I suppose a lot of the fun has gone out of it; there isn’t that air of mystery any more”

“Sometimes being limited can make things stronger,” agrees Honer. “It makes you think more concisely about what you’re doing. Whereas nowadays it’s so easy to keep adding things and adding things, and unless you’ve really got discipline, you can get yourself in a pickle.”

“We were moving between technologies”, he says when looking back at the making of the album. “Things were changing quickly.”

It was a transitional time for the city too.

Sheffield in 1999 was still firmly in the shadow of deindustrialisation. The Full Monty had come out two years prior. Unemployment rates had fallen from their 1980s peak, and the city was starting to grapple with a new, post-industrial identity. If a new civic pride was emerging, it was doing so underneath the weight of economic depression. I was, meanwhile, a five year old growing up in Norfolk, and had no real concept of South Yorkshire beyond ChuckleVision, so I ask Dean and Parrot to fill me in on Sheffield back then.

“It was a declining city,” says Parrot. “But it still had lots of cheap spaces that you could use, and a solid little community of musicians that were scratching a living.”

“It was easy to find rehearsal spaces,” Honer adds. “And it was easy to make your way doing music or art, without having to do a full-time job.”

Jarvis Cocker had long been part of that tight-knit local scene, and close friends with the group members. By the time Pickled Eggs and Sherbert was being made Pulp had hit mainstream success and were busy touring the US, but it was a phone call from Parrott that brought Cocker back to Sheffield.

In the liner notes to the album Cocker recounts his memories of the creative process, describing his collaboration as a chance to return to his roots. Those hoping to hear the full details will not have to fork out for the physical release, as the streaming version includes an audio rendition of his liner notes, read in Cocker’s unmistakable dulcet tones.

“Listening back to the album now I’m struck by how much some of the lyrics I wrote deal with my recent brush with pop stardom and my attempts to re-engage with my home town”, he says. “This is the album that brought me back down to planet Earth. And you know what? It’s out of this world.”

The songs also proved popular in the unlikeliest of quarters, with the young Britney Spears re-recording her own rendition of ‘Beat Goes On’ for her debut album.

“If you listen to that album, it sticks out like a sore thumb,” laughs Honer. He explains how they had only agreed to the collaboration on a whim. “I’m glad it’s one of the ones we agreed to do, because we were quite big-headed at the time. We had no idea she would turn into such a massive star.”

In some ways, it seems an odd connection, between a dingy bedroom studio in Sheffield and the sleek world of a nascent American popstar. But really, it’s those connections between pop’s mainstream and its fringe elements that form the lifeblood of this album. Out-and-out dance tracks like ‘Sweet Music’ sit next to songs like ‘Stars On Sunday’, with its haunted music hall refrains. Bizarrely, the whole thing works. Twenty six years on from its initial release, this “weird little album” is still in a field of its own.

The remastered and expanded Pickled Eggs and Sherbet is out now