I spent half a year working in a hospice. I joined in a bitterly cold February, the roof intermittently capped with snow. I watched as the first daffodils emerged in the hospice garden, and I left not long after the summer heatwave saw temperatures pushing forty degrees.

This is a story of change. It is a story about the ways in which we register change, attempt to predict it, and draw meaning from its vagaries.

Over those six months, I watched as people grappled with their ailing bodies. I watched shifting currents of emotion coalesce around the dying person. I watched life as it sped up and slowed down, behaving in ways that were at some times coherent and predictable, at others irritational and capricious.

The story of change is one that Adrianne Lenker tells with precision on ‘Change’, the opening track of Big Thief’s Dragon New Warm Mountain I Believe In You. It is a song that considers change in its many facets: in relationships, in the shifting seasons and weather, in life and death. Big Thief were a constant companion during those months. The album was released as I started the post, and I played it endlessly in my car as I drove to and from work each day, making the commute home at first in the early dark of winter evenings, later in broad summer daylight.

Seeking sanctury

These photos are taken from the album art of the vinyl release. The band recorded much of the album in a secluded cabin in the forests of upstate New York, surrounded by birdsong and trickling streams. The album art is a collage of love and laughter. There are shared meals with close friends, fireside jams, recording sessions with Lenker’s dog scampering around the studio. Life stripped back to essentials, to things that matter. In many ways these photos speak to the aims of the hospice movement. Food, company, peaceful surrounds – concerns that become central to those faced with dwindling time.

Much like that woodland studio, the palliative care unit at Sheffield’s Northern General Hospital is situated at a deliberate remove from the bustle of the acute wards. It is a small sanctury separated from the main hospital by a well-tended garden, a stretch of tarmac, and a gulf in medical practice. Things are run differently here. Most of the time, questions asked by doctors are technical in nature – how has the machinery malfunctioned, and how can it be rectified? In palliative care we focussed on different, altogether more humanistic questions – how do you feel as a person? How can we make things better? And given that time is short, what are your priorities? Palliative care is branch of medicine defined by the ethos of its practitioners more than any particular organ or life stage; it is a call to put social, emotional and spiritual needs on an equal footing to physical symptoms. It aims to get the big conversations out of the way early, leaving room to work out what matters most, and how best to use the time that remains.

As a junior doctor on the unit, part of my role was to admit new patients and write up an initial plan. It was a joy to ask patients about their smoking and drinking habits not with the intention of encouraging them to cut back, but of organising a last pint or crafty cigarette. Visiting rules were much more relaxed than in the main hospital, and pets were allowed too – I soon made a point of routinely enquiring about pets in the hope of having something cute and fluffy to brighten up the ward round. Moving from the world of acute medicine, there was a profound shift in the things valued and prioritised by staff, and I gladly settled into this alternate culture.

With limited hospice beds, we could only take the most complex patients. Complexity was judged holistically, taking into account both symptom burden and the broader human picture. Many of our patients were young. The young tended to carry a higher level of psychological complexity; no one expects to find themselves preparing for death whilst on the cusp of a long-planned retirement, or in some cases still raising a young family. We bore witness to final chapters riven with drama – there were deathbed reconciliations with long-estranged children; there were weddings on the ward held by the hospital chaplain.

That all said, palliative medicine is not just a matter of being nice. Every one of our patients had advanced, terminal disease, so there was by definition more pathology to be found here than anywhere else in the hospital. Our patients were as sick as those on intensive care, but the intensity and invasiveness of medical intervention had been paradoxically reversed. This was not simply a place for medical care to be withdrawn – it was a place where medical care was more carefully weighed and considered. Palliative care is also not just a case of doing nothing and letting nature take its course. Occasionally we did press ahead with blood tests and antibiotics, but these were always tempered by careful thought and discussion with patients rather than kneejerk intervention. Comfort was always the central question. At times we could be invasive in the pursuit of comfort – inserting drainage tubes into swollen abdomens, hoping to relieve the discomfort caused by the accumulation of fluid. The medical and nursing teams were only part of the endeavour. Chaplains, social workers, physiotherapists, psychologists: a whole team at hand to help navigate the stormy waters of loss and grief.

An old adage

So, that is a little of what palliative care does and its niche within the health system. I will not focus here on palliation itself, on the ways in which symptoms such as pain, nausea or breathlessness can be relieved. Instead I will focus on the dark art of prognostication – predicting the future course of an illness. Suffice to say that prognostication itself can be an act of palliation; an attempt to ease the psychological burdens of uncertainty.

Trouble is, we so often get it wrong.

Even the most senior nurses on the unit, with decades of experience, were sometimes way off. Some patients who I thought were in the last few days were still alive weeks later. On one occasion I told a family that there was perhaps a week to go, give or take. They all went home for the night, and the patient quietly slipped away that evening. In the days that followed, angry at my misjudgement, I became the most gloomy prognosticator, calling families in at the slightest hint of deterioration. Any prognosis you receive from a doctor will be coloured by any recent experiences like this, by their own insecurities and fears. Like most, I had a tendency to err on the side of caution. Better a premature visit from that cousin in Cornwall than leaving it too late and no visit at all. When we caveat our predictions with layers of uncertainty, we really do mean it.

So how do I attempt to answer a question that most terminally ill people will ask at some point – how long have I got left? The underlying disease process does matter, and more on that later. But the overarching principle of prognostication is much broader than this. It can be summarised in an adage passed down through medical education, summarised something like this:

The rate of change predicts the prognosis

To understand exactly what is meant here, consider a woman diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer. Having been landed with this devastating news, she sets about driving herself across the country, paying last visits to cherished places and people. Over months, there are subtle signs of change. Weight and appetite start to drop off. Where once she had run marathons, a walk to the corner shop becomes a struggle. Soon she can scarcely leave the house.

The old adage tells us that if these changes are occurring month by month, the terminally ill person probably has months left to live. If things are changing week by week, they probably have weeks.

Lenker points to the differing paces of change in the opening lines of her song:

Change, like the wind

Like the water, like skin

In the dying process, change itself tends to accelerate – which would logically follow if the old adage is true. The housebound woman with breast cancer becomes bedbound. Soon, we are in the rhythms and rituals of the deathbed. People are then changing day by day, sleeping more and more of the day before slipping into a peaceful state of deep unresponsiveness, their breathing patterns then changing hour by hour in the final moments.

Those final days are in many ways reminscient of the rituals of birth. This is hardly an original observation. Many cultures have the established role of a ‘death doula’, a kind of ‘death midwife’ present to guide patients and families through life’s final stages. Having witnessed both childbirth and death, I’d have to pick death if given the choice of the two experiences. Though some people suffer diseases that themselves cause pain or other symptoms, dying itself is not a painful or unpleasant process. Most deaths are peaceful declines, moving with the predictable patterns of a labour, progressing through accelerating stages until reaching that inevitable endpoint – a breath, either the first or the last.

Not everyone came to the hospice to die. Many would spend a few weeks having their medications tweaked and symptoms stabilised before returning home. Some ultimately planned to spend their last days at home, whilst others would come back later on in their illness. On their return, familiar utterances would crop up in the nursing handover.

“Margaret is back again, have you been to see her yet? She’s really changed.”

I try and convey something of this pattern when answering the question of time. I talk about the changes that they will themselves notice, I talk about what to expect. I ascertain two facts that matter infinitely more than any particular blood test or scan: I gain a measure of what a person can do for themselves – the independence their body affords them – and a measure of how quickly their level of function has changed. When informed of these patterns, patients and families can themselves recognise when things are moving faster or slower than initially expected.

Like the leaves

Change, like the sky

Like the leaves, like a butterfly

Death, like a door

To a place we’ve never been before

The natural world often features in the names and symbols of palliative care services. In part this is a matter of euphemism. As a rule, it seems that the darker the subject matter of a service, the more abstract its name. But in the images of falling leaves and wilting flowers there is a nod to rhythms and cycles common across nature. Whatever their illness, the dying by and large fall into predictable rhythms in their last days, changing as reliably as the leaves.

In ‘Change’ Adrianne Lenker leans into these timeless generalities, patterns and resonances, producing something that sounds like an ancient folk riddle, a song we can scarcely believe is new. It could easily be a Pete Seeger ballad, or an Anglican hymn sung in school assemblies. The gently strummed chords are warm and diatonic, the lines follow neat rhyme schemes. It sounds innocent, almost childlike in its wide-eyed simplicity, something she has previously addressed:

“I’m becoming more fearless. I definitely had a desire for things to be complex: Is this chord progression too simple? Is this lyric too simple? Is this cliché? Is this corny? I feel less of that noise in my head, and more of just, “This is what I want to sing.” In ‘Change’ I felt it was just straight-up my 7-year-old self writing it: “Change like the sky/Like the leaves/Like a butterfly.” It’s the dance between my child self and my older, mother self, always in conversation.”

Lenker is a rare songwriter who knows the weight of things but carries them lightly. Profound and eternal utterances sit aside puns and imagistic observations. There are serious romantic stares with healthy doses of laughter. Her approach to songcraft is open-hearted and reverent; the resultant art is unparalleled in its tenderness and intensity.

Four paths

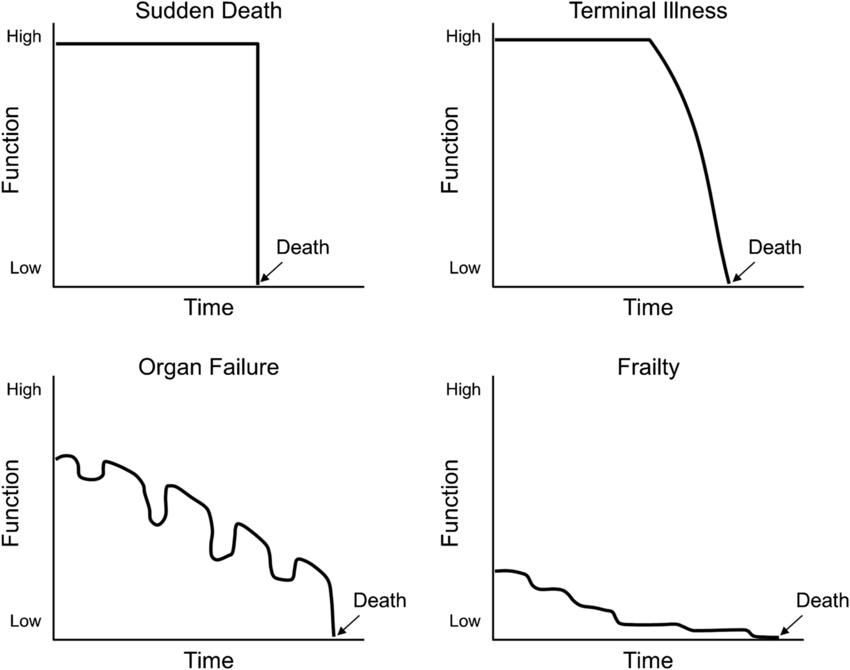

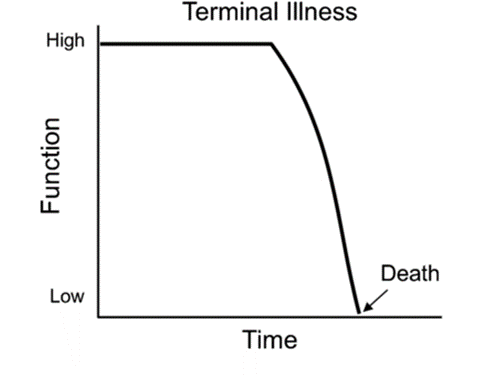

We had a steady stream of medical students passing through the hospice. When it came to prognostication, as well as the old adage, I also passed on one of the most useful graphs in medical education. It traces the four main paths by which people approach the end of their lives. Here it is:

These plots show function and independence changing over time for four broadly defined patterns of pathology. As a general tool for contemplating the future, there is no better guide. I’ll consider each in turn.

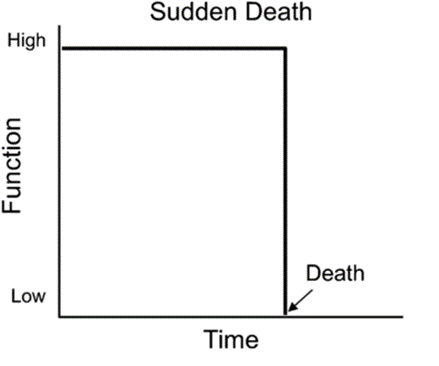

Sudden death

We used to gather at the windows when we heard the whirr of the helicopter blades, watching the huge machinery descend, bringing a wave of wind in its wake. In a strange juxtaposition, the hospital’s helipad sits directly opposite the palliative care unit. Patients arriving via this route can then be wheeled straight into resus, often going on to emergency surgery or intensive care. Helicopter ambulances are an emblem of medicine at the peak of its powers: all high drama and life-saving heroics.

A small minority of our patients had come to us through this kind of path. Something terrible had happened, and every intervention in the hospital had been tried to no avail. A car collision, a massive stroke, or a perforated organ that the surgeons couldn’t fix. This is really the only time where palliative care and active treatment should be viewed as a dichotomy, of ‘doing everything’ then ‘keeping them comfortable’. In the other three trajectories there is much more room for nuance; ‘being on palliative care’ can and should mean myriad things.

People sometimes say they’d prefer to go this way – suddenly and with little warning. As much as this avoids a protracted period of ill health, it means no opportunity to say goodbyes or tie up loose ends. The bereaved are left with a grief complicated by things never said, of stories cut short mid-chapter.

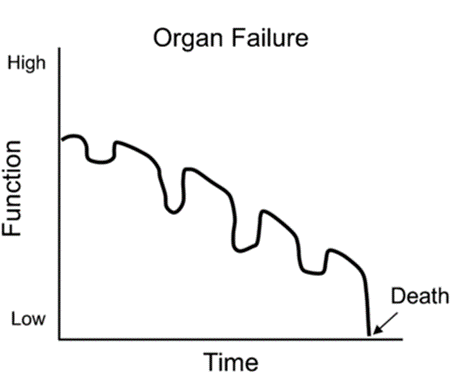

Organ failure

The jagged path here is cut by a failing organ: smoke-damaged lungs wheezing through another infection; a failing heart letting the legs and lungs fill with fluid; the cirrhotic liver slowing to a temporary halt, leaving the blood awash with waste. With the ensuing treatment the body is dragged back to some of kind of equilibrium, but with diminishing returns each time. Reserves and defences deplete, and at some point there comes a final precipitous dip to death, the body declaring enough is enough, the other organs following suit. Most of these patients die in the acute setting, with active treatment continued often until the very end. It can be an impossible task predicting which illness will be the last, and some patients make recovery after miraculous recovery; others spiral faster than expected.

Medicine is always a transaction. For the most part, a straightforward deal can be struck: the patient gives up their sleep to allow the incessant monitoring of their physical parameters, their veins are interrogated daily, tubes are put where tubes do not belong. In exchange, doctors give patients time and good health. This is a bargain that falls apart at the extremes; in the final stages of an illness a lot can be given for very little gain. Those that came to us on the palliative care unit had grown tired of the sight of needles and drips, declaring themselves ready to go when their latest illness had rolled around.

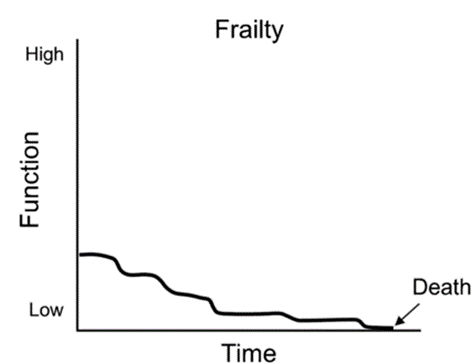

Frailty

In this pattern, both body and mind trace a slow and uneven decline over a number of years, moving in fits and starts, good days and bad days. These are frail, elderly patients, often with dementia and a host of other medical issues. They tend to have a long period of poor health towards the end of their lives.

One third of people in a general medical hospital are in the last year of their life. That is an astonishing statistic. But for a place where death is commonplace, it often remains unnamed and unmentioned. Without a frank discussion of the future, doctors, patients and families find themselves in a conspiracy of silence. The conversation stays centred around treating or correcting this or that blood result, whilst the person at the centre of it all grows visibly weaker as the months go by. All involved have some sense of what is really going on, but no one feels quite ready or able to bring it up.

Some of this reticence comes from the fact that this is the area in which doctors are most often proved wrong. The disease course of dementia is characterised by ups and downs; other physical illnesses can also have the effect of worsening confusion and agitation levels. In some cases, infections and illnesses have opposite effect: patients appear sleepy, uninterested in food or drink, and in some cases become totally unresponsive. This can look remarkably similar to the patterns of natural dying, only to prove reversible when the underlying cause is addressed.

Cancer

This is the exponential entropy of cancer. Other terminal illnesses like motor neurone disease follow a similar path. There is a snowballing of decline, with little in the way of recovery. The relatively predictable change of cancer explains why cancer and hospice care are so closely linked, and why there is still an occasional misconception that hospices only look after people with cancer.

John did not expect to end up on the palliative care unit when he went to A&E with vomiting and severe abdominal pains. A scan on the surgical ward showed a blockage in his bowel caused by numerous cancerous growths. The surgeons deemed it inoperable, but there had been talk of a biopsy and chemotherapy.

The palliative care specialists were invited to the ward, initially to help manage his pain which had not abated even with regular doses of morphine. Patients in neighbouring beds were making slow recoveries from major operations. John hoped to do the same, and was talking of living for years with treatment. To the trained eye, it was clear that he probably wouldn’t live to see the results of a biopsy, let alone undergo a gruelling regime of chemotherapy. He had grown weak and barely able to leave his bed. The change had been rapid, and he was now able to do very little for himself. It was clear that time was short.

John made the trip across the tarmac. There were some big conversations to get through. There was a shift of focus in his medical care. Pain and nausea were his main concerns, so they were ours too, and with the right medications things were manageable. He seemed happier away from the clamour and constant beeping of the busy surgical ward; everything felt a little more humane. He had a view of the gardens; the daffodils were out. He grappled with his situation, and thanked us for our honesty when the topic of time had come up. Family appeared from far and wide. His wife had a camp bed in his room. When it was clear that drips and antibiotics were making no difference, we stopped them rather than doubling down. His wife didn’t get a last minute phone call and a violent resuscitation attempt; there was no hollow reassurance that ‘we did everything we could’. Instead she held his hand throughout his last days, staff on the unit guiding her through John’s gradual lull into a deep unresponsiveness. Within a week of arrival on the unit, he had died peacefully.

Blue Lightning

Modern medicine works wonders. But when faced with incurable disease it can become an instrument of torture. One role of palliative care is to act as a bulwark against the excesses of medicine and against the medicalisation of life’s final stages, always pointing back to the person at the centre of it all. It matters in those final deathbed days, but its scope stretches back far before this; it has a role to play from the moment of diagnosis.

No one expects doctors to predict the trajectory of an illness with perfect accuracy. But in giving some indication of the road ahead, we can give time to make plans and say goodbyes. In ‘Blue Lightning’, the closing song of that Big Thief album, endings, partings and goodbyes abound:

Angelia took a photograph

The moment had to die

Years later, like an epitaph

We read it and we cry

This mornin’ I went to have a bath

The water ran dry

Clear warnin’, has it come at last?

The time to say goodbye

The album closes with a dark quip, an amalgam of lightness and heaviness sat tightly together in Adrianne Lenker’s final lyric, repeated over strains of jubilant guitar:

Yeah, I wanna live forever ’til I die

There could be no better motto for palliative care and what it hopes to achieve.

3 responses to “Like The Water, Like Skin: Change, Palliative Care and Big Thief”

Hi Tom,

Reading this at 3:25 in the morning unsuccessfully trying to lul a baby to sleep. This is so beautifully written.

Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Tom. Our mum’s are good friends. I’m currently sat at the end of my dad’s bed. His name is John and he was diagnosed with a collapsed or twisted bowel. He came into the hospital on Monday morning, and by Tuesday given an end of life care plan. His condition is changing almost hourly. He’s being well looked after by the medics who have followed the focus of your blog to a tee. I had dinner with my mum this evening and she asked again: have you had time to read Tom’s blog. I hadn’t, but I’ve got all the time in the world right now. As I spend hours, not days with my dying dad. I feel better placed to understand how my dad, and indeed the family, are being supported. For that, I thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I cried reading this, especially the part about John. Beautifully written.

LikeLiked by 1 person