“I’ve been goin’ through somethin’”

This is how Kendrick Lamar opens his fifth album, and by the end of the eighteen song saga there is no doubting his claim. The Compton-born rapper has kept a low profile in the five years since his last major release; he has started a family and, as we find out over the course of the album, has been tackling some deep-seated psychological issues. Mr Morale & The Big Steppers is a many-faceted beast, but at its core it is a story of personal growth and redemption.

“I hope I’m not too late to set my demons straight” he raps on ‘Die Hard’, “I know I made you wait, but how much can you take?” These hints of darkness haunt the first half of the album. On ‘United In Grief’ Kendrick tells us he “grieves different”. The conventional sounds of grief – choirs, mournful piano – give way to a frenetic drum beat and tales of Kendrick’s hedonistic abandon. Sex and spending are ways to paper over grief, though the exact sources of grief remain unnamed. From time to time the voice of Whitney Alford, Kendrick’s fiancée, crops up between songs on the first disc of this double album, imploring him to go to therapy and address his issues head on.

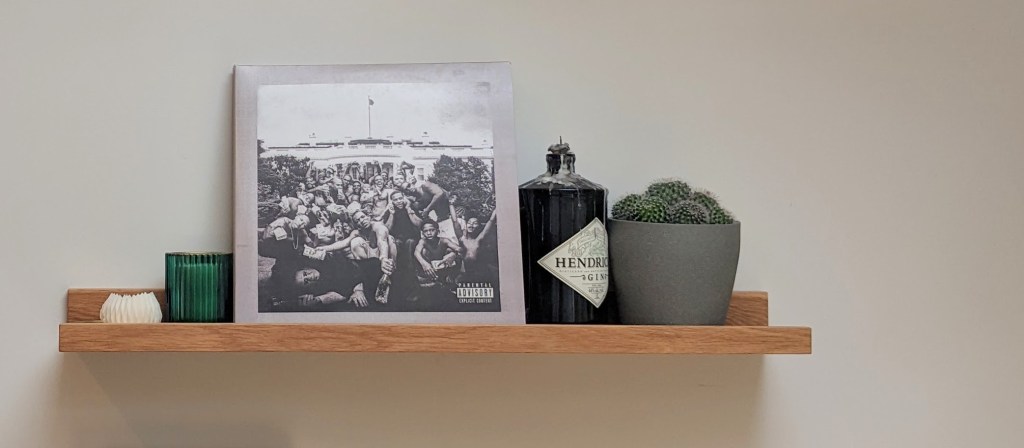

Early tracks also explore Kendrick’s experiences of fatherhood. His family appear on the album cover in a striking photograph composed like a Renaissance painting. In the background Kendrick’s fiancée and son recline in a Madonna and child pose, whilst Kendrick stands in the foreground with his daughter in his arms and a crown of thorns on his head. This image encapsulates the album’s central themes: family, fatherhood, and collective redemption through acts of suffering. Thematic cohesion has always been one of Kendrick’s greatest strengths, and this is yet another album of unerring vision and focus. There are many threads woven through this weighty body of work, but none get lost, and not a word is wasted.

‘Father Time’ tells stories of “grown men with daddy issues”. Whether through their absence or presence, the fathers on this track leave a trail of strife and maladjustment. Masculinity in general goes up on trial, with Kendrick describing the harms of emotional repression as he watches his father put on a brave face and rush back to work after a bereavement. Kendrick is not simply pointing fingers here, and speaks candidly of his own infidelity and sex addiction on a number of tracks.

‘We Cry Together’ is a six minute skit not for the faint-hearted, in which an arguing couple wage nuclear-grade verbal war on one another. The personal turns political as the feuding couple bring R. Kelly and Harvey Weinstein into the argument. There is talk of “fake feminists” and “real victims”. It isn’t clear whether any of the opinions espoused by these characters are Kendrick’s own, or if he simply showing us the ugliness of contemporary public discourse as it disintegrates into a vicious shouting match.

‘Auntie Diaries’ has already generated its fair share of controversy. On the one hand the song represents a watershed moment, as perhaps the first major rap release to take on transphobia. Kendrick looks back to his youth and tells us about his transgender relatives and the prejudice they faced, particularly from their local church, but appears to repetitively misgender and deadname his relatives in the process. A Twitter storm has inevitably ensued. To suggest that Kendrick’s misgendering comes from a place of ignorance is to assume that a Pulitzer-winning rapper has somehow overlooked the nuances of language. A more charitable and likely explanation is that we are meant to be looking through the eyes of a younger Kendrick, perhaps a little uneasy with his relatives’ revealed identities, and unsure of the terminology he should be using. Listen carefully and you will hear him adopt the correct pronouns as the song develops. In fact, he uses the track to make a broader point on the power of language. We are left feeling deliberately uncomfortable by his abrasive and repetitive use of a homophobic slur, as Kendrick himself cringes at the way it would once slip casually off his teenage tongue. He considers how the N-word sounds in the mouth of a white person, and has a moment of revelation. This song is not a cheap moment of virtue signalling, but an authentic account of allyship – full of internalised prejudices and privileges, but open-hearted and ready to learn from the direct experiences of marginalised groups.

Kendrick’s daddy issues seem not to extend to the biggest daddy of them all. The natural progression from ‘Father Time’ would be to paint God as an absent father, whether through his negligence or non-existence. This thought is not entertained and Kendrick’s faith is as strong as ever. Suffering from writer’s block, he asks not so much for divine assistance, but for the chance to act as a conduit for God’s word: “I asked God to speak through me, that’s what you hear now, the voice of yours truly”. This is Kendrick as prophet, as God’s mouthpiece – a claim that would sound absurd coming from the mouth of anyone less talented. He later uses the track ‘Savior’ to temper these assertions of divine inspiration, and warns his followers not to blindly trust or idolize any particular individual. This is his “I’m not the Messiah” Life of Brian moment if ever there was one. In ‘Crown’ Kendrick looks ahead to a day when the praise and attention will someday wane, viewing the scenario with a degree of relief.

He is at pains to tell us that he doesn’t want to ‘do’ social media, celebrity appearances at rallies, or quick soundbites for the latest cause célèbre. He has largely ducked out of five politically tumultuous years to work on himself, and the views he expresses on this album have presumably been mulled over rather than churned out. When he does hold forth on identity politics there are sentiments that will stir up both the right and the left, but Kendrick’s intention is always to ask difficult questions, contextualise and empathise, rather than preaching dogma.

On the opening of the second disc, Kendrick relents to Whitney’s pleas and agrees to go to therapy. We have heard about his sins and vices, and now it is time to delve into the roots of his pain. His fiancée’s voice is replaced by that of German self-help guru Eckhart Tolle, who Kendrick met back in 2020.

As the album’s narrative reaches a climax in ‘Mr Morale’ and ‘Mother I Sober’, we are drawn back to the notion implied by the album cover: Kendrick as a Christ-like Man of Sorrows. Kendrick bears witness not only to his own past, but to the collective experience of the Black community as a whole, considering how slavery and racism have fed into cycles of generational trauma. “I’m sensitive, I feel everything, I feel everybody”, he raps in the first lines of ‘Mother I Sober’ – telling us how he must inherit the burdens of his ancestors.

This notion of vicarious experience is central to all of Kendrick’s work. Each of his personal experiences are a microcosm of a wider phenomenon; each opinion and idea is refracted through a wider cultural lens. Kendrick’s view of the human condition is one built on dialogue and connection, and no musical genre can achieve this sense of interconnectedness quite like hip-hop, with its endless run of quotations, samples, guest artists and collaborators that create a tapestry of shared cultural experience.

Through therapy, he starts to talk of transformation. His daughter can be heard in the outro, thanking him for breaking the cycle of suffering. It is lyrically one of his most emotionally honest pieces to date, spoken in gentle tones over sombre backing, and by the end there is not a dry eye in the house. Collective demons are exorcised, transgressions are forgiven, and grace is delivered. He has been going through something, and now he has gone through it. It is done.

If ‘Mother I Sober’ is the Passion, then ‘Mirror’ is surely the Resurrection. In this triumphant ode to self-love and self-care, Kendrick casts aside his saviour complex to focus on his own inner peace, proclaiming “I choose me, I’m sorry” again and again, over the sounds of a Pharrell Williams beat and swan-diving violins. If personal growth takes hard work, then this is its glittering prize.

With over an hour of fast-paced flows and guest spots, there is much to digest here. Kendrick’s albums are a knotty tangle of code and metaphor, and this double album will continue to bear fruit with every listen. The music itself is as dense and lush as the lyrics that have formed the focus of this review. Over time, the Dissect Podcast will probably release a series pulling apart each line on the album, and the Genius website will annotate every reference and quote, but for now we can indulge in the feast of a new Kendrick Lamar album. If the closing song is anything to go by, Kendrick has made it clear that his priorities now lay with his burgeoning family, and his own happiness, rather than an ambition to maintain the musical world-domination he has already achieved. He has the money, he has the critical acclaim. He could happily retire now. We can only hope he doesn’t.